Recently I gave a talk at Nottingham Contemporary on a panel about Object-Oriented Ontology (OOO). The other panelists were Francis Halsall and Graham Harman, and the round table discussion afterward was moderated by Francis Love and Andrew Goffey. The evening started with a great video art piece by Elizabeth Price, User Group Disco. You can watch the entire set of talks on YouTube. Below I’ve pasted my notes and some of the images I showed, to give you a sense of what my talk was about — it’s a bit faster than watching the video. Click on any image to enlarge it.

How the art world deals with objects: archives

The Andy Warhol Archive in Pittsburgh plays host to basically everything that Warhol ever owned, including 610 boxes referred to as “time capsules”. Our late Uncle Andy had a habit of tossing things in boxes by his desk, and then when they were full, sealing them up, dating them, and putting them aside. Some very odd things have been found in these boxes. Entire pizzas. Slices of birthday cake. A mummified foot. Et cetera. At the Glenn Gould Archive in Ottawa, similar odd collections of personal effects linger on. The pianist’s trademark gloves and caps, of course, but also, a collection of all the hotel keys he ever pinched from the hotels he stayed at during his concert career.

Of the items in Warhol’s boxes, Tom Sokolowski, Director of the Andy Warhol Museum, says: “Everything in his life, in an artist’s life… was meritorious of recollection”. I wonder if it is. I speculate that I would gain no insight into Warhol from being able to handle an old pizza that Warhol purchased, never consumed, and then put in a box. I doubt that seeing Gould’s hotel key collection would tell me much about his character, though maybe I’d notice which hotel chain he liked best.

But this is how it goes in the art world: the holy of holies, the hand of the artist, dictates what is important, not whether or not the objects themselves are of genuine cultural significance. At first I thought hanging on to Andy Warhol’s pizzas and Glenn Gould’s hotel keys was absurd – just throw them in a 3D scanner in case a scholar really wants to know what Andy took on his pizza later on and dump the original. I thought it was messy, un-curated, un-critical and maybe even lazy. Now I see it a little differently: once in the cardboard box, or in Gould’s apartment, an ontological levelling took place and the pizza is on par with the wig; the keys are on par with the piano. It’s perhaps impossible to say what clues will be unearthed from these objects. From any object.

How I have dealt with objects in my own curatorial practice (sometimes)

The way that thought, as it is expressed through language, intersects with thought as it is expressed through material forms is a central curatorial concern of mine. Particularly today, when artists collaborate with and are influenced by such a wide variety of actors, including philosophers and scientists, understanding this intersection and creating productive frameworks where these worlds meet is arguably one of the key functions of a curator.

In the case of the exhibition and eBook developed under the name Speculative Realities, I was intrigued by the recent continental philosophical turn towards materialism and the object. I think that concepts put forward by Object-Oriented Ontology and Speculative Realism hold great potential for spurring a conversation about how philosophical thought can be in dialogue with, or provide additional insights into and context for, contemporary modes of art production.

What brought me to the point of considering this particular interaction between philosophy and art was the experience of co-curating the anchor exhibition of the Dutch Electronic Art Festival 2012, which was themed The Power of Things. The exhibition was an overt investigation of materialism and objecthood, and was influenced by Jane Bennett’s Vibrant Matter, vitalist philosophies, and the idea of ‘vital beauty’ as described by John Ruskin. For an exhibition that still might be classified as a ‘media art’ or ‘electronic art’ exhibition (indeed we still use the term ‘Electronic Art’ within the name of the festival itself) it was remarkably lacking in glowing screens and interactive experiences that required triggering sensors. Instead, the exhibition hall was mostly filled with objects: a ball made up of all the naturally-occurring elements on earth (Terrestrial Ball by Kianoosh Motallebi), a nano-engineered artwork composed of the “blackest black” (Hostage Pt. 1 by Frederik de Wilde), a sculpture made of salt and ice that changed over time (Sealed by Jessica de Boer), and numerous other examples.

Following the construction of this exhibition, containing such a range of materialities and posing different questions and challenges to the viewer, it struck me as an obligation to examine the questions that were raised by this exhibition further. And so I began to eavesdrop on the international conversation that has been taking place about Speculative Realism and Object-Oriented Ontology. Something about the return of the thing and thinking beyond the human realm is capturing imaginations beyond the halls of philosophy where these ideas tend to reside. The draw of such thought to the arts is also pronounced. As art critic Rahma Khazam observed: “Although SR [Speculative Realism]’s counter–intuitive theses and dismissive attitude towards humanity in general have their detractors, [but] for its supporters in the art world, the mental gymnastics it imposes are part of its appeal.“

Certainly for me, the allure does lie in a fundamental shift of curatorial thinking, to reconsider relationships between material and immaterial processes, and between ‘matter’ and ‘what matters’. Plus the object is in a bit of a crisis. From Uncle Andy’s factory (and the shambles of “verification” of which objects were actually fashioned by the artist or his deputy) to Damien Hirst’s hundreds of assistants that push processes of commodity production to its most eccentric limits, we have observed how in step the art market is with broader processes of globalisation. It is worth bearing in mind then, that despite our radical impulses in some fringes of the art world, we too are subject to the same forces.

So I decided to dive in. Blowup, which I launched as a label at V2_ in 2011, is a series of events and exhibitions that investigates topics ranging from art for animals to speculative designs for future objects, etc.

Inspired by OOO and Speculative Realism, I commissioned two artists and one collaborative duo to make new artworks reflecting broadly on concepts within Object-Oriented Ontology and Speculative Realism. The artists were Tuur van Balen & Revital Cohen, Cheryl Field, and Karolina Sobecka.

My curatorial process involved close conversations with a range of artists who were already looking at notions of non-human-centredness, or materialism, or a democracy of things in their work. Throughout the commissioning process, I dialogued with the artists and gave them texts (in particular, each artist received a PDF of Levi Bryant’s The Democracy of Things) and I waited some time before revealing the identity of the other artists to any particular artist. In this way, the works were developed autonomously, without any collaborative dialogue around the actual production process or outcome.

The final exhibited four works, while substantially different, also had several points of convergence.

(C8H8)n, CSi, KAl2(AlSi3O10)(F,OH)2, C, C, CaSO4, Fe3C, SiH3(OSiH2)nOSiH3 by Cheryl Field

(C8H8)n, CSi, KAl2(AlSi3O10)(F,OH)2, C, C, CaSO4, Fe3C, SiH3(OSiH2)nOSiH3 by Cheryl Field

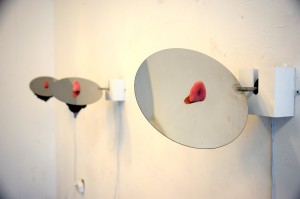

Neither Ready Nor Present To Hand by Cheryl Field

Nephology 1: Cloud Maker by Karolina Sobecka

A fundamental return to and concern with nature became apparent; mountains, clouds, and living plants figured strongly in the group of works. Interestingly, a wry sense of humour can also be perceived in each work: the absurdity in Cheryl Field’s disembodied fingers and tongues; the chance interactions with random landowners in Karolina Sobecka’s Cloud Maker experiments; the sheer stretch of the imagination involved in Tuur van Balen and Revital Cohen’s night garden for communication between hares and the moon.

Finally, it is worth noting that while we laboured on producing this exhibition and conducting interviews for the accompanying eBook, interest in the wider world in this philosophical turn manifested into other exhibitions simultaneously: Resonance and Repetition, curated by Rivet in New York; Things’ Matter, curated by Klara Manhal in Vancouver; and The Return of the Object, curated by Stefanie Hessler in Berlin. What this suggests in anyone’s guess, but to me it signals that grappling with the concepts and consequences of these philosophical movements has been assumed as a priority for art of this moment.

How curators deal with objects (sometimes)

The art world is generally not good at this levelling thing in a broad sense. However things have, and continue to, open up bit by bit. Art and design are no longer necessarily consigned to different museums. The art formerly known as new media is coming out of obscurity and into the MoMA’s collection.

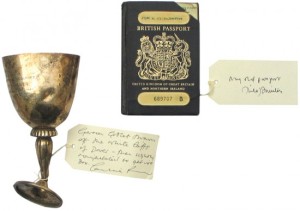

The Maybe, 1995 at Serpentine Gallery, curated by Tilda Swinton and Cornelia Parker, included Tilda Swinton sleeping in a glass box as an artwork, alongside Napoleon’s rosary, one of Churchill’s cigars, and as pictured here, one of Tilda Swinton’s expired passports and a goblet thrown from the cliffs of Dover.

Images: Top: from The Brain, Bottom: from The Maybe

“The Brain” in the Fredericanum at dOCUMENTA (13), curated by Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, included objects like Eva Braun’s compact powder and other objects to display and map out a partial range of the curator’s thought.

Rosemarie Trockel curated an exhibition at the New Museum in New York in 2012 entitled “A Cosmos” presents an imaginary universe in which Trockel’s own artwork from the past thirty years is juxtaposed with objects and artifacts from different eras and cultures representing many of her artistic interests.

Of course it goes without saying the exhibition on now at Nottingham Contemporary, The Universal Addressability of Dumb Things curated by Mark Leckey also fits this pattern: drawing attention to form and meaning without asking an artist to sanctify each object. An unsigned urinal is just a urinal, or is it?

The Last Word (goes to an artist)

Joseph Kosuth, One and Three Chairs, 1965. A chair, an image of a chair, and the dictionary definition of chair presented together. A consideration of the object at its best, I’d say – how is the definition different than the image, the object? Materially of course there are many differences, but all are deeply connected to the same concept. And perhaps most challenging, it’s not Kosuth’s chair, Napoleon’s chair, Hitler’s chair or Lady Gaga’s chair, it’s just a chair selected and photographed by the institution that installs the piece.

Of course instruction works not just by Kosuth but by others, has been followed by other genres of works pushing limits of materiality, like the example of Tino Seghal raised in the first talk tonight by Francis, and so it is worth remembering that while the art market may largely revolve around objects, whole areas are also unconcerned with or openly reject them. In a way the curatorial act is always also simultaneously an artistic instruction work, placing objects and designing experiences. And if we as curators can reconsider the object, on its own, inspired by OOO and related philosophical movements, the range of expression we present to the public can only benefit, and become more complex and more subtle.